Orbital Angular Momentum

October 2, 2020 12:57 pmFree quantum particles can posess a property which seems to defy classical physics. Namely they can orbit around a central axis without a restoring force, which is schematically illustrated below (b). This property known as free particle orbital angular momentum has been observed in photons, electrons and recently also neutrons. We are investigating the latter for applications in neutron scattering, quantum information and quantum contextuality. If succesfully generated in neutrons orbital angular momentum would represent the 4th available degree of freedom in neutron quantum information/contextuality experiments (in addition to spin, energy and position information).

Quantum angular momentum (OAM) has been known for over 100 years. For an undergraduate student the most notable example is found in the hydrogen atom. Here we classify the angular momentum of the system into spin angular momentum, defined by the quantum number and orbital angular momentum, defined by the azimuthal and magnetic quantum numbers. The former is an intrinsic property of fundamental particles, while orbital angular momentum describes the orbital motion of said particles. In the case of constituent particles like neutrons the intrinsic spin is the sum of the spins and orbital angular momenta of its constituents.

The Orbital Angular Momentum Operator and its Eigenstates (OAM in free space)

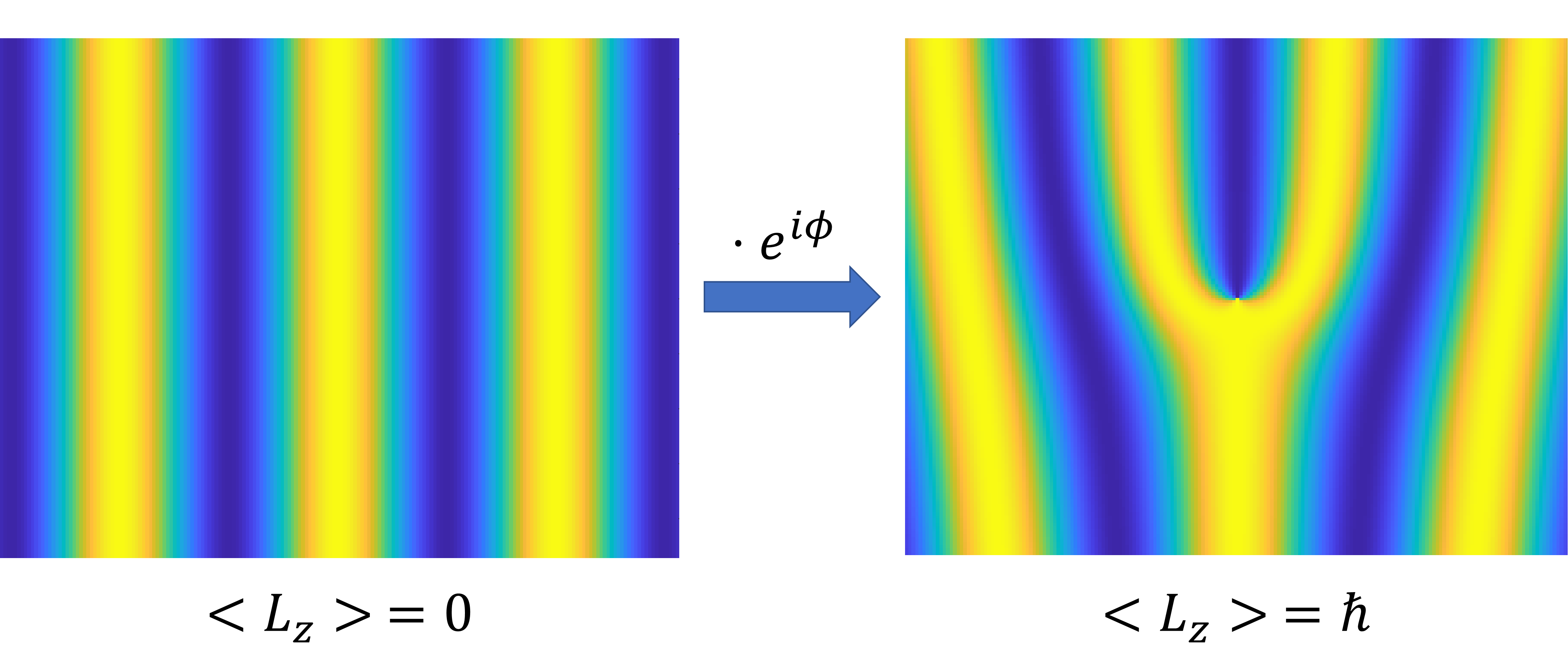

The quantum mechanical OAM operator is given by the cross product between the position and momentum operators expressed as . As we will se soon, in cylindrical coordinates we can focus on the z-component since this is the only component that produces a non-zero expectation value . This operator has the Eigenfunctions , also referred to as vortex functions, with where , the OAM mode number, being integer to satisfy the continuity conditions . Soon we will see that the OAM eigenfunctions are also eigenfunctions of the free space Schroedinger equation. Before moving on it is useful to explore the OAM carried by planewaves, starting from a planewave propagating in the y direction . Using the definition of the OAM operator we can determine its expectation value for instance . So planewaves carry OAM locally in the directions perpendicular to propagation (with OAM density , but when averaged over all space the mean OAM of a planewave is zero.

These vortex functions are also Eigenfunctions of the free space Schroedinger equation in cylindrical coordiantes:, since the second derivative in the azimuthal coordinate is simply , which obviously has the same Eigenfunctions like . Using the ansatz with and we get the Bessel equation , which has the Bessel functions of the first kind as solution.

Therefore, the eigenfunctions of the Schroedinger equation in cylindrical coordinates can be written through superpositions or more precisely , where denote the Bessel function, with . Therefore the kinetic energy of these Bessel waves is given by . For visualization the transverse profile of a Bessel beam with and see below (note that the ring at consists of 50 dark and 50 light fringes equal to the mode number of the Bessel beam).

In order to determining OAM density we start by writing the OAM operator using cylindrical coordinates:

Next we convert the Cartesian vector to a cylindrical one in form of as . Now applying this operator to plane wave solutions to determine the cylindrical OAM density of Bessel beams

Since both the and components are odd functions it follows that is the only non-zero component of the OAM expectation value expressed as . Pure Bessel beams therefore only carry OAM along the z-axis, the axis of propagation.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Orbital Angular Momentum

Generally there exist two types of OAM; that is OAM that depends on the choice of the coordinate system called extrinsic and OAM that is to a degree independent of the coordinate system called intrinsic. In the intrinsic case OAM emerges from the non-locality of the wavefunction, the fact that wavefunctions can have structure.

In the case of localized point particles, the OAM they carry must be a consequence of the coordinate system and hence must be extrinsic. Or explained in a more mathematical way: it can be demonstrated by looking at what happens to the OAM operator and its expectation value under translation . As discussed above, in cylindrical coordinates the only non-zero component of is the z-component and for a localized particle is zero. It follows that classical particles can only carry extrinsic OAM.

Since intrinsic OAM must be translation invariant and for Bessel beams only the z component of the OAM expectation value is non-zero we have to determining what properties a wavefunction must have to possess that ensure that is translation invariant. So let us examine the divergence between the z component of the translated OAM operator and the untranslated operator , which gives and determine its expectation value for am arbitrary wave function first. This leads to the following two conditions for intrinsic OAM:

So if the momentum components perpendicular to the OAM are zero, the OAM can be considered translation invariant and therefore purely intrinsic. Next we examine whether or not the OAM Eigenfunctions satisfy this condition, by substituting them for  and transforming the integrals to cylindrical coordinates:

since they are zero it follows that the OAM Eigenfunctions carry intrinsic OAM.

Now we consider an arbitrary superposition of OAM Eigenfunctions given by

which is the case for all and the conditions reduce to

which is only ever the case if , which leads to the curious conclusion that superpositions of OAM Eigenfunctions can only carry purely intrinsic OAM if the superposition does not consist of any spatially overlapping neighbouring modes, which is illustrated below.

Insets (a)-(c) contain non-neighboring superpositions (a) =50, (b) =50; =52, (c) =50; =53; =56; = 59, while (d)-(f) show superpositions of different numbers of neighboring modes: (d) =50; =51 (e) =50; =51; =52 (f) =50; = 51; = 52; = 53. In case of neighboring superpositions of OAM the intensity distribution localizes to one side of the plane, indicating a preferred propagation direction. When the superposition does not contain neighboring mode there is no localization to one side of the plane, hence there is no preferred propagation in the x or y direction. This figure demonstrates that superpositions of neighboring modes localize to one side of the plane, indicating a pre- ferred Cartesian propagation direction. As the number of neighboring modes in the superposition increases the intensity distribution begins to localize to a point. At this point we want to emphasise that if a state carries extrinsic OAM, this does not necessarily imply that the state or its OAM is not ”quantum”.

Transverse and Longitudinal Orbital Angular Momentum

The OAM orientation is defined by the propagation axis. Hence we can define longitudinal OAM, where the OAM is parallel to the propagation direction and transverse OAM, which is perpendicular to propagation.

Orbital Angular Momentum Preparation

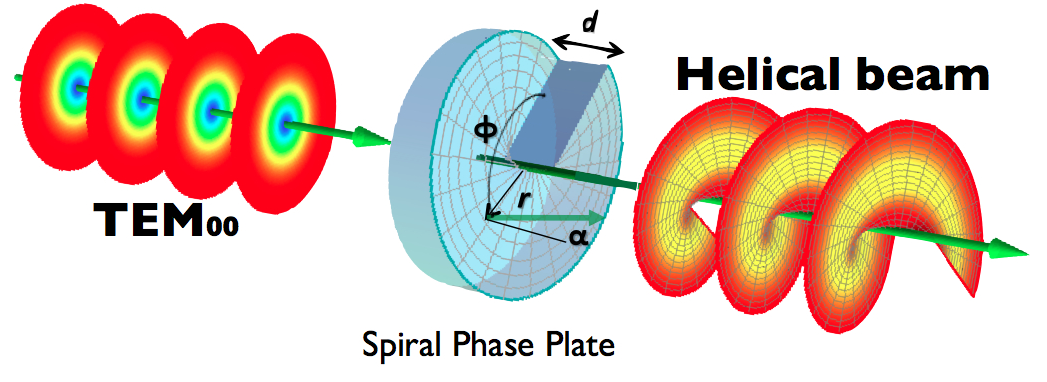

As discussed above, a particle carrying a single (or multiple) unit of orbital angular momentum can simulateneously be in an eigenstate of the free space Schroedinger equation. In other words an eigenfunction of the operator can simulataneously be an eigenfunction of the free space Hamiltonian: . So rather strangely quantum mechanics predicts that a free particle can orbit around the component of its momentum vector in the absence of any restoring forces. As is often the case in physics interesting mathematical expressions have real world counterparts. In 1991 such twisted wavefronts, carrying a single unit of OAM, were observed in free photons. Starting from a superposition of azimuthal modes non-linear effects in an optical medium were exploited to filter the modes 1. It was not until 1994 that a pure mode could be converted to a different single integer mode. This was accomplished by means of a spiral phase plate (see figure below) 2. An SPP is simply an optical medium whose thickness varies azimuthally such that a wave packet passing through the center of an SPP picks up an azimuthal phase.

Schematic of a spiral phase plate which transforms a photon with no OAM into a twisted vortex beam carrying non-zero OAM.

While interesting in itself, the phenomenon of photon OAM can be understood classically with the theory of electromagnetism and the Maxwell equations. It wasn’t until 2010 that orbital angular momentum was detected in free matter waves 3. These states were generated in electrons using an electron microscope and a spiral phase plate constructed out of graphite thin films. Orbital angular momentum has also been observed in a more limited way in neutrons 4. This first observation was accomplished in a neutron interferometer using an aluminum spiral phase plate. In contrast to electrons and photons where the orbital angular momentum is intrinsic, that is where the quantization axis of the OAM is parallel to the component (i.e. the mean propagationd direction) of the particle momentum, the neutron OAM observed to date is extrinsic, where the quantization axis of the OAM is defined by the normal vector of the spiral phase plate or beam twister device.

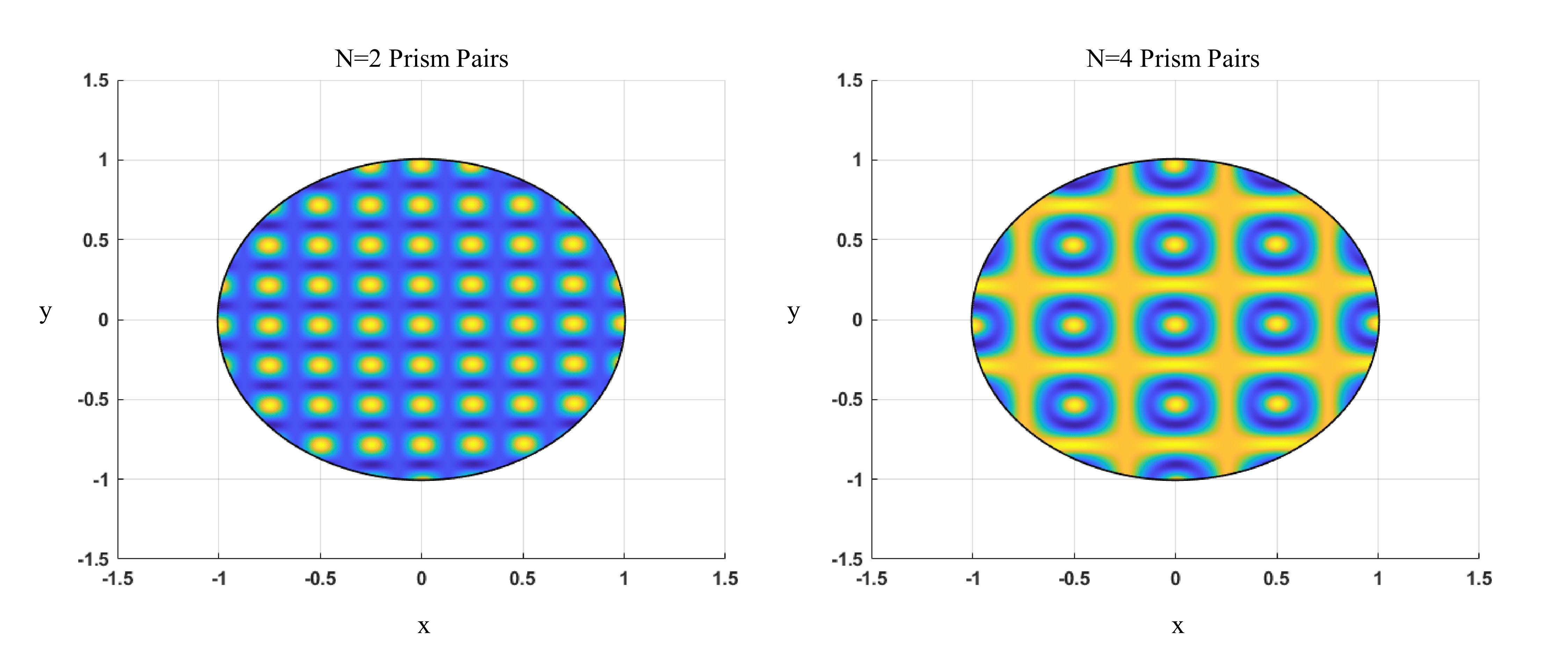

Since that time additional methods for generating neutron OAM have been discussed and developed. Here we focus on the techniques which not only generate OAM but also entangle said degree of freedom with the neutron spin, thereby generating spin-orbit states. We will start by looking at the two closely related magnetic techniques. The first of which is the quadrupole magnet 5, which couples to the neutron magnetic moment, via the Zeeman effect: , where is the gyromagnetic ratio and are the Pauli spin matrices. The quadrupole field is simply given by a gradient in and direction . Working out the potential we find , or in cylindrical coordinates where the entangling action between spin and OAM becomes more clear: , where and are the spin and OAM raising/lowering operators respectively. The second magnetic technique for spin-orbit production in neutrons makes use of a series of magnetic prism pairs 6. The prism effectively creates a one dimensional magnetic gradient, as opposed to the two dimensional gradient seen in the quadrupole 7. The fields of each prism in one pair are orthogonal to one another. According to the Suzuki-Trotter expansion an infinite series of such pairs would mimic the quadrupole action. If cut off at a lower bound a phase diagram of spin orbit lattice states are generated 8, 9. Such a phase diagram is shown below in the figure below. If the coherence length of the test particle is sufficiently large these states are intrinsic. For neutrons however both the quadrupole and the gradient method generate extrinsic orbital angular momentum, since the neutron coherence length is much smaller than the beam size. While extrinsic spin-orbit states are certainly useful for neutron small angle scattering experiments like in SEMSANS, there is still a need for intrinsic OAM states for other scattering experiments and quantum information.

Depiction of the lattice states resulting from two pairs of magnetic prisms (left) and four pairs of prisms (right)

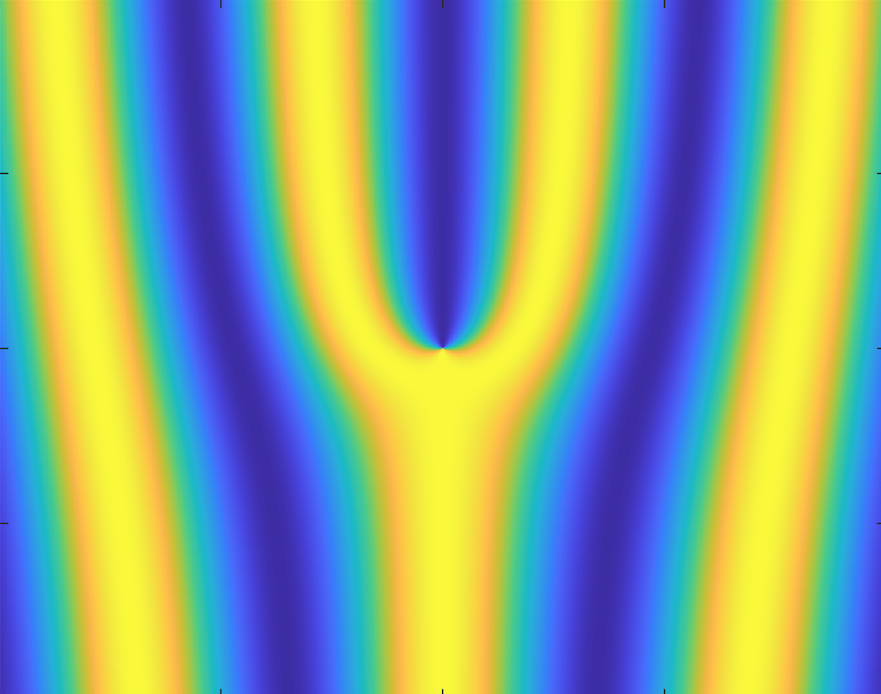

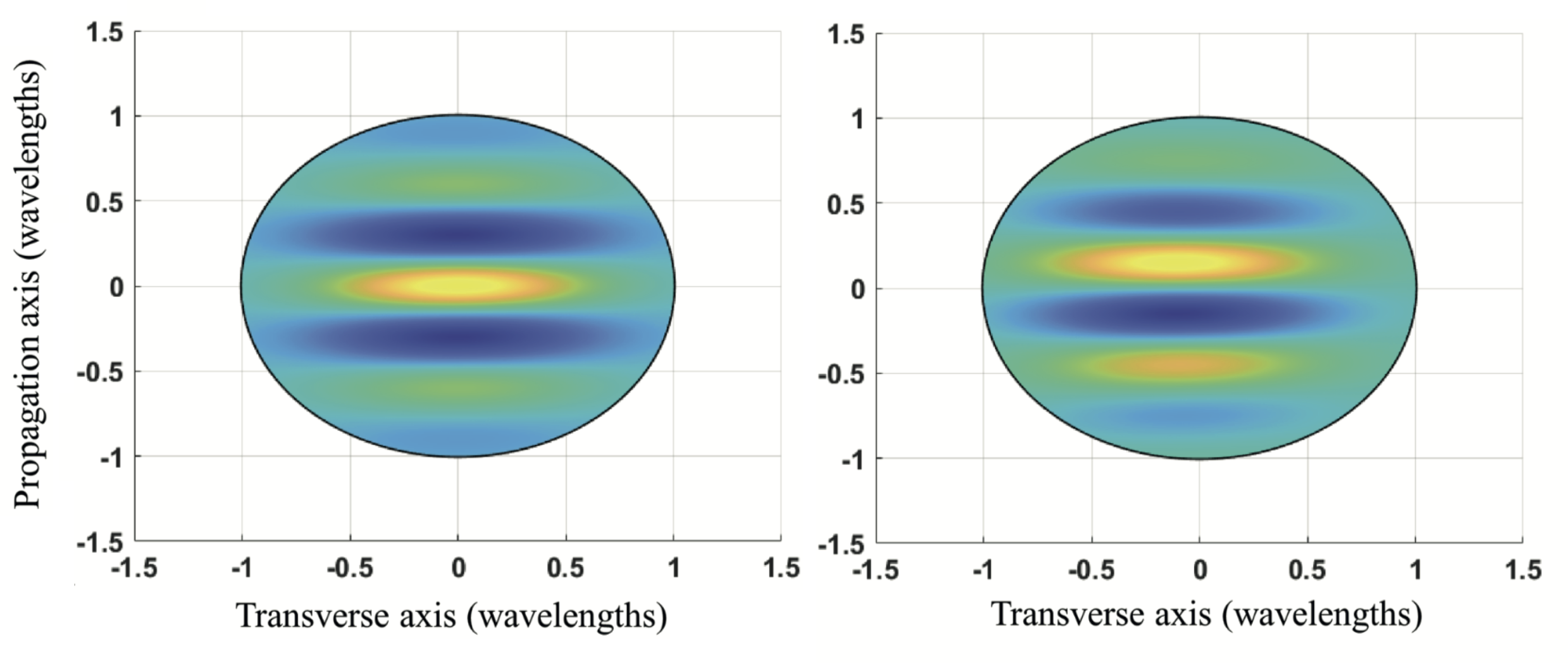

Up to this point we have discussed various methods to generate intrinsic and extrinsic orbital angular momentum states in free neutrons. All of these states are longitudinal, that is to say, the quantization axis of the OAM is parallel to the propagation direction. A question arises on whether or not orbital angular momentum of free particles can be transverse to the propagation direction. The Schroedinger equation for free particles in vacuum seems to predict that the answer is yes! Looking at the simple planewave solution in cylindrical coordinates , which can be expanded as an infinite series of cylindrical modes carrying OAM according to the Jacobi Anger expansion . The expectation value for transverse OAM of the plane wave is zero, however we can multiply the solution by the OAM raising operator , thereby shifting the expectation value and the index by one: As shown at the beginning of this document this is also a solution of the free space Schrödinger equation and this solution has an average transverse OAM of one unit of . This planewave carrying one unit of transverse OAM is shown below in a figure. We expect that these transverse OAM states can be generated in neutrons which are traversing a transversally polarized static electric field.

If instead of plane waves Gaussian wave packets are considered we get the following picture for the same scenario:

References:

1. F. T. Arecchi, G. Giacomelli, P. L. Ramazza, and S. Resider, Vortices and Defect Statistics in Two-Dimensional Optical Chaos, Physical Review Letters 67 (1991) 3749-3752. ↩

2. M. W. Beijersbergen, R. P. C. Coerwinkel, M. Kristensen and J. P. Woerdman, Helical-wavefront laser beams produced with a spiral phase plate, Optics Communications 112 (1994) 321-327. ↩

3. Masaya Uchida and Akira Tonomura, Generation of electron beams carrying orbital angular momentum, Nature (London) 464 (2010) 737-739. ↩

4. Charles W. Clark, Roman Barankov, Michael G. Huber, Muhammad Arif, David G. Cory and Dmitry A. Pushin, Controlling neutron orbital angular momentum, Nature (London) 525 (2015) 504-506. ↩

5. Joachim Nsofini, Dusan Sarenac, Christopher J. Wood, David G. Cory, Muham- mad Arif, Charles W. Clark, Michael G. Huber, and Dmitry A. Pushin, Spin-orbit states of neutron wave packets, Physical Review A 94 (2016) 013605. ↩

6. R. Pynn, M.R.Fitzsimmons, W.T.Lee, P.Stonaha, V.R.Shah, A.L.Washington, B.J.Kirby, C.F.Majkrzak, B.B.Maranville, Birefringent neutron prisms for spin echo scattering angle measurement, Physica B 404 (2009) 2582–2584. ↩

7. D. Sarenac, J. Nsofini, I. Hincks, M. Arif, C. W Clark, D. G. Cory, M. G. Huber and D. A. Pushin, Methods for preparation and detection of neutron spin-orbit states, New Journal of Physics 20 (2018) 103012. ↩

8. D. Sarenac, D. G. Cory, J. Nsofini, I. Hincks, P. Miguel, M. Arif, Charles W. Clark, M. G. Huber, and D. A. Pushin, Generation of a Lattice of Spin-Orbit Beams via Coherent Averaging, Physical Review Letters 121 (2018) 183602. ↩

9. D. Sarenac, C. Kapahi, W. Chen, C. W. Clark, D. G. Cory, M. G. Huber, IvI.ar Taminiau, K. Zhernenkova, and D. A. Pushin, Generation and detection of spin-orbit coupled neutron beams, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 116 (2019) 20328–20332. ↩

10. J. Schwinger, On the Polarization of Fast Neutrons, Physical Review 73 (1948) 407–409. ↩

11. Niels Geerits and Stephan Sponar, Twisting Neutral Particles with Electric Fields, ArXiv:2007.03345 (currently under review). ↩

12. L. Allen, M. Babiker and W.L. Power, Azimuthal Doppler shift in light beams with orbital angular momentum, Optics Communications 112 (1994) 141-144. ↩

13. J. Leach, M.J. Padgett, S.M. Barnett, S. Franke-Arnold, and J. Courtial, Measuring the orbital angular momentum of a single photon, Physical Review Letters 88 (2002) 257901. ↩